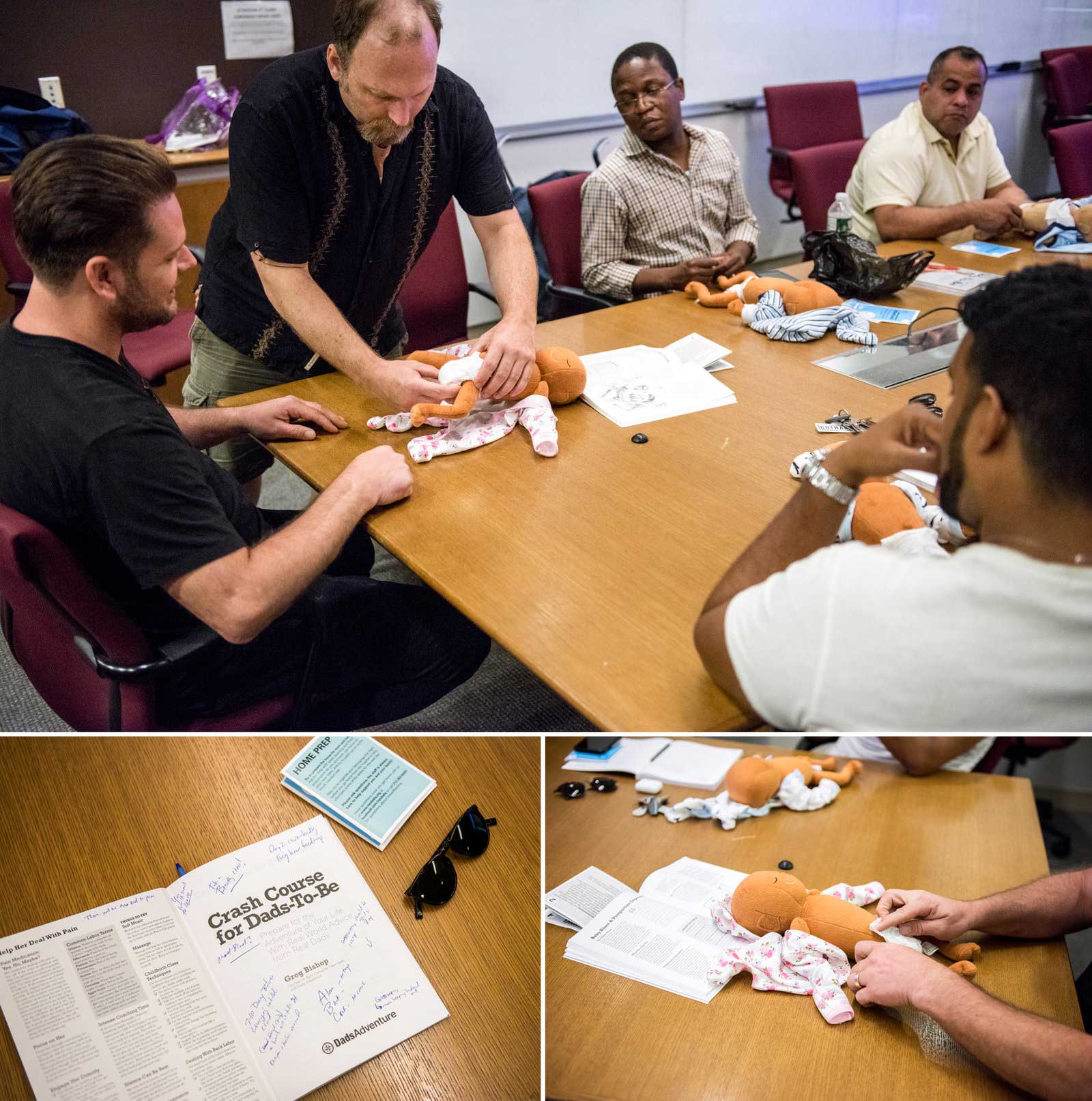

VIEW LARGER Joe Bay (center), coach of a New York City "Bootcamp for New Dads," instructs Adewale Oshodi (left) and George Pasco in how to cradle an infant for best soothing.

VIEW LARGER Joe Bay (center), coach of a New York City "Bootcamp for New Dads," instructs Adewale Oshodi (left) and George Pasco in how to cradle an infant for best soothing. "Before I became a dad, the thought of struggling to soothe my crying baby terrified me," says Yaka Oyo, 37, a new father who lives in New York City. Like many first-time parents, Oyo worried he would misread his newborn baby's cues.

"I pictured myself pleading with my baby saying, 'What do you want?' "

Oyo's anxieties are common to many first-time mothers and fathers. One reason parents-to-be sign up for prenatal classes is to have their questions, such as 'What's the toughest part of parenting?' and 'How do I care for my newborn baby?' answered by childcare experts.

With that focus, "Dad's parenting questions can fall to the wayside," says Dr. Craig Garfield, a professor at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine and an attending physician at Lurie Children's Hospital in Chicago. And the lack of attention to a new father's needs can have ripple effects that impact the whole family — in the short-run and later, Garfield says.

Around the U.S., a number of health care providers, such as Garfield in Chicago and the non-profit Bootcamp for New Dads in New York City, have begun trying to change their approach to such classes. Some go so far as to hold single-sex prenatal classes specifically for men."Because each parent holds a separate role in their child's life, expectant mothers and fathers may seek different answers to their parenting questions," Garfield explains.

Indeed, raising children is nothing new, but parenting culture has shifted in the U.S. over time. For instance, compared to parents of the 1960s, today's mothers and fathers tend to focus more of their time and money on their children, a recent study suggests, adopting what sociologists call an "intensive parenting" style.

Parental worries about their kids' academic success and future financial stability may drive this parenting philosophy, researchers say.

These mounting responsibilities can stress the family, which is why mothers and fathers may feel eager to define their parenting roles. While a new mother's role in modern society is often directed by her baby's needs to breastfeed, cuddle and sleep; a new father's role isn't always spelled out.

VIEW LARGER Dads-to-be learn how to change diapers in the workshop for and by men, at the New York Langone Medical Center. Participants say they appreciate the combination of concrete skills and candid advice from other fathers.

VIEW LARGER Dads-to-be learn how to change diapers in the workshop for and by men, at the New York Langone Medical Center. Participants say they appreciate the combination of concrete skills and candid advice from other fathers.

"Even though fathers are far from secondary in their children's lives, they may feel uncertain about their place in the family," says Julian Redwood, a psychotherapist in San Francisco who counsels dads.

In fact, Garfield says, as they await their baby's arrival, men, like women, often worry about the hands-on tasks of childcare, how to raise well-adjusted kids, and how to cope with sleep deprivation, especially after they return to work.

Addressing those concerns early helps dads get involved with parenting from the outset, and that bolsters the whole family's health — maybe especially the baby's — according to research by pediatricians and child psychologists. For example, a 2017 study found that the amount of hands-on, sensitive engagement that dads were observed to have with babies at age 4 months and 24 months correlated positively with the baby's cognitive development at age 2.

Early father involvement also benefits the health of the child by fostering sturdier father-child bonds and psychological resilience, researchers say.

Oyo says the three-hour-long, Sunday Bootcamp for New Dads session he attended at NYU Langone Medical center, helped ease his early fears. At the peer-led workshop, "I learned babies communicate through crying," he says, "and that they usually cry for four reasons — which made infant care seem less scary."

Joe Bay, a 44-year-old father who lives in Clifton, N.J., was the session's coach. Calling the course a "bootcamp" acknowledges the ambivalent relationship dads may feel between childcare duties and societal views of masculinity, Bay says. It also speaks to the practicality of what the men can expect to learn -- how to hold a tiny baby, for example, or how to soothe a crying infant.

Participants also learn how parenthood can rock their partner's well-being — and upend their own emotional health, as it rattles their sense of identity.

Future fathers get a chance in the course to question Bootcamp grads. Bay says he finds many fathers-to-be more willing to open up when their partners are absent. Oyo concurs.

"I met a dad who seemed like a 'pro' with his infant son, which was reassuring," Oyo says. Learning from that man how to change a diaper and how to swaddle a baby, he says, helped him stay calm later when facing his own wailing daughter. In the class he'd learned how to "read her cues."

As the dads get more secure in their parenting skills, the moms usually become less anxious, too. And that's crucial in making sure a behavioral tendency family scientists call "maternal gatekeeping" doesn't derail the family system.

"Maternal gatekeeping encompasses a set of behaviors that mothers may use — consciously or unknowingly — that limit the father's involvement with their children," explains Anna Olsavsky, a doctoral candidate in human development and family science at The Ohio State University, and lead author of a 2019 study of how such gatekeeping influences a budding family.

Gatekeeping behaviors can be small but powerful: micromanaging dad's interaction with the baby, for example, or criticizing how he holds or feeds the child.

Though fathers have always been somewhat involved in their children's care, Olsavsky says, society still deems mothers "childcare experts."

"That portrayal can lead dads to be socialized into supportive parenting roles" she adds — in other words, they take a step back.

In their most recent study, Olsavsky and her colleagues found that men who felt welcomed by their partners to participate in child rearing felt more connected to their partners, and were more likely to identify as equally involved and responsible co-parents.

Gatekeeping behaviors can be small but powerful: micromanaging dad's interaction with the baby, for example, or criticizing how he holds or feeds the child.

Though fathers have always been somewhat involved in their children's care, Olsavsky says, society still deems mothers "childcare experts."

"That portrayal can lead dads to be socialized into supportive parenting roles" she adds — in other words, they take a step back.

In their most recent study, Olsavsky and her colleagues found that men who felt welcomed by their partners to participate in child rearing felt more connected to their partners, and were more likely to identify as equally involved and responsible co-parents.

Guests of the class Jesse Applegate (center) and his son, Jacob, field questions from Saxon Eldridge (left), and Chris De Souza (right) about what to expect after the baby's born.

Guests of the class Jesse Applegate (center) and his son, Jacob, field questions from Saxon Eldridge (left), and Chris De Souza (right) about what to expect after the baby's born.Oyo, whose daughter is now 9 months old, says the bootcamp helped him take an active lead in parenting. It was also a relief to his pregnant wife, he says, to see that he was studying up for fatherhood.

"After the course," Oyo says, "I shared everything I had learned, and once the baby was born, I became the trusted source for swaddling."

Garfield tells prospective fathers that the art of proper swaddling, a method of wrapping babies that soothes them in the first couple of months, can be one of "dad's secret parenting weapons." Additional tools include using a low voice to talk or sing to the baby, Garfield adds, or playing with the newborn during diaper changing time.

Learning these parenting techniques and the dynamics that develop when one new parent feels sidelined can be just as useful for adoptive parents and same-sex couples, Bay notes.

For all parents, raising children can feel a bit like being thrust into an ocean without knowing how to swim. But having an outlet where each caregiver can connect and learn from their peers helps make parenting less lonely. And it dismantles the myth of the perfect parent.

Greater parental harmony can help decrease spousal friction, which tends to rise when sleep deprivation and a lack of control are at an all-time high.

Reducing parental bickering pays off for the baby, too: Research suggests constant arguments can have an impact on a child's brain development, disrupt healthy attachment, and raise a child's risk of becoming anxious and depressed later in life.

Many mothers and fathers enter the wild ride of parenting hoping to be expert parents. That's a big mistake, Bay tells participants in his Bootcamp workshops.

"I always tell dads the goal isn't to be 'perfect,' " he says, "but 'good enough.' "

Juli Fraga is a psychologist and writer in San Francisco. You can find her on Twitter @dr_fraga.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.