VIEW LARGER Installation view of Joseph Wright of Derby's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, in "Science and the Sublime: A Masterpiece by Joseph Wright of Derby."

VIEW LARGER Installation view of Joseph Wright of Derby's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, in "Science and the Sublime: A Masterpiece by Joseph Wright of Derby." One went from California to London; the other, from London to California. No passports were involved. But the two museums where the paintings are housed — the Huntington Art Museum near Los Angeles, and London's National Gallery — are welcoming visitors to see these masterpieces.

The best known is a portrait of a rosy-cheeked fellow, maybe 15 years old, in a blue satiny suit with matching blue bows on his shoes.

VIEW LARGER The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788). Post-conservation photo.

VIEW LARGER The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788). Post-conservation photo. A British fellow, he'd spent a century in the Huntington, near Pasadena, Calif. When he first left London back in 1921, 90,000 people came to say goodbye. Some wept. Still, he's had a good run at the Huntington, the star of the museum.

"It's the one thing everybody wants to see," says the Huntington's director, Christina Nielsen. And maybe take home images of him, for souvenirs. "There are lamps, pepper grinders, ashtrays," she says.

Thomas Gainsborough's 1770 painting has been reproduced on all kinds of tchotchkes. And why not? The kid's adorable, and getting a nice welcome back in England. "Blue Boy, right now, is wowing London audiences," according to Nielsen. Meanwhile the National Gallery in London loaned the Huntington one of their most popular 18th century paintings: Joseph Wright of Derby's massive 1768 work, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump.

VIEW LARGER Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768, oil oncanvas,72 x 96 1/16 in. Presented by Edward Tyrrell, 1863.

VIEW LARGER Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768, oil oncanvas,72 x 96 1/16 in. Presented by Edward Tyrrell, 1863. A mad "scientist" — probably a traveling lecturer — with a flowing red robe and glowing long, white hair holds up a big glass bubble. There's a beautiful white bird inside the bubble. A lid makes the bubble airtight. The experimenter turns the crank on a vacuum pump that's attached to the jar — stay with me. He pumps out the air. The bird looks distressed.

"The poor cockatoo is unable to breathe!" exclaims Melinda McCurdy, the Huntington's curator of British art. "And if air is not let back into the jar soon, that bird will, unfortunately, die," she giggles.

What's so funny? Two little girls at the lecturer's round wooden table are horrified! One covers her face, can't look. Their grandfather tries to comfort them. Curators point out that Charles Darwin's grandpa is also there; he's watching along with other science fans. A young couple, though, just looks at one another. "They're really not paying attention to the scientific experiment" says McCurdy. Of course not! They're in love.

The most interested of the 10 observers, in a green jacket, holds a big watch. He knows how long it will take before the bird asphyxiates.

"I'm hoping that he's gonna watch his watch and say, 'time to let the air back in,'" McCurdy says, giggling again.

Well, that would be a relief, tortuous as it appears. But what's going on? What's the red-robed fellow and his audience doing?

It's a scientific experiment. They're studying the nature of air: what it does, what depends on it. 1768 was the Enlightenment, a time of empirical observation, experimentation, technology — and showbiz. The old man isn't a real scientist. He and others like him are showmen, entertainers.

"These guys would travel around and give demonstrations in peoples houses," McCurdy explains. That's how they earned their livings. So the cockatoo couldn't die; they were expensive. The pseudo-scientist could lose money replacing them. Thus the watch, the release, the bird back in the big air-filled bubble.

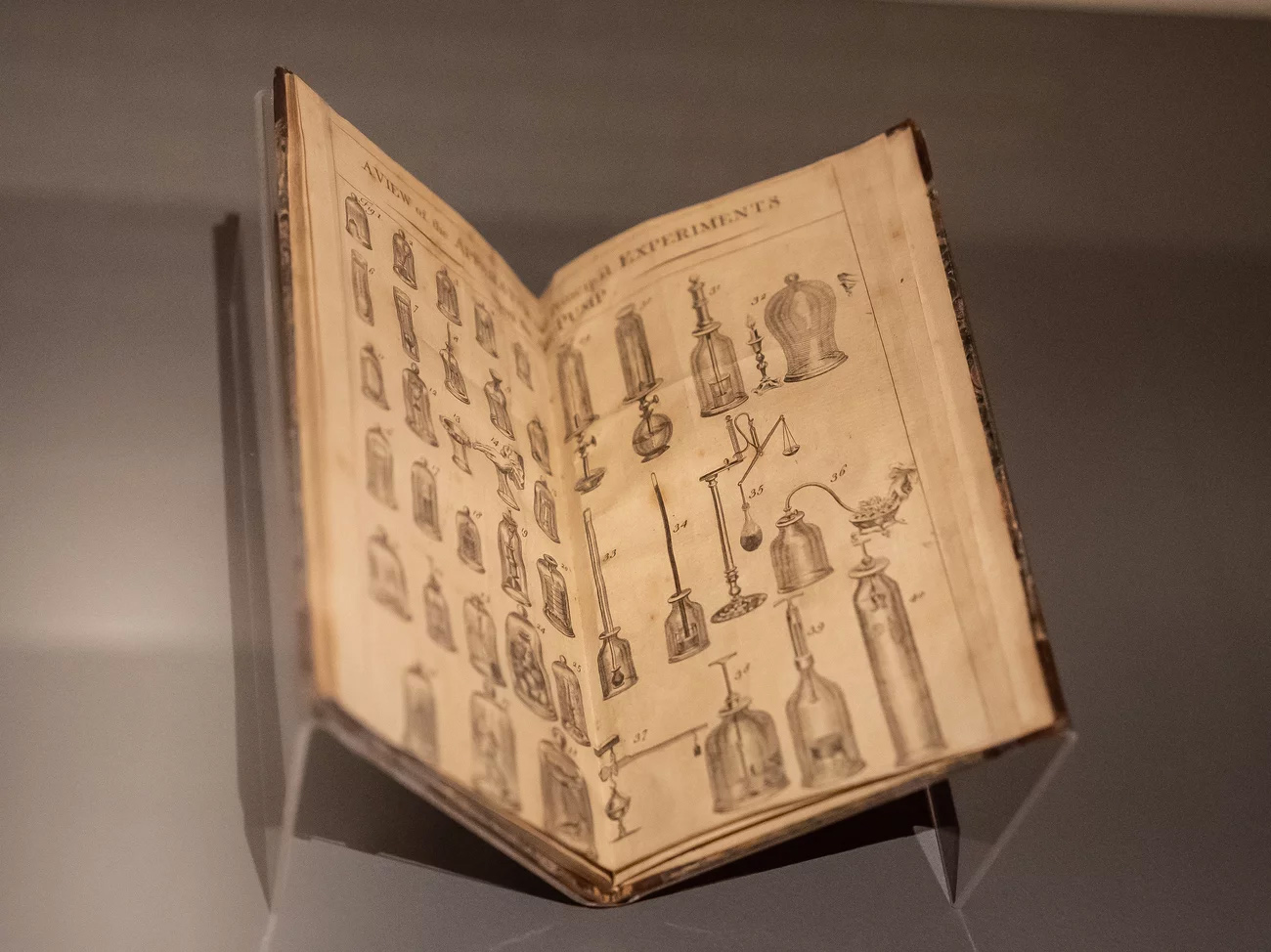

VIEW LARGER Installation view of Benjamin Martin's The Description and Use of a New, Portable, Table Air-Pump and Condensing Engine. With a Select Variety of Capital Experiments manual, in "Science and the Sublime: A Masterpiece by Joseph Wright of Derby."

VIEW LARGER Installation view of Benjamin Martin's The Description and Use of a New, Portable, Table Air-Pump and Condensing Engine. With a Select Variety of Capital Experiments manual, in "Science and the Sublime: A Masterpiece by Joseph Wright of Derby." And Brits bought their own air pumps to do their own experiments — instruction booklets included. (I mean, there was no Real Housewives in 1768!) This was real entertainment, back then.

"And if you notice the lecturer is looking straight out at the audience," McCurdy points out. "He's the only one making eye contact with us. It's almost as if he's asking us, 'should I let the air back in?'"

Yes! Let in the air! And then thank Joseph Wright of Derby for capturing the scene in his masterpiece — on display now at California's Huntington Art Museum.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.