Better understanding the motivations of top-dollar donors.

Better understanding the motivations of top-dollar donors.

The Buzz for August 18, 2023

The 2024 election is still more than a year away, but campaigns are already in full swing. Candidates are at work attempting to gain support from voters, or, perhaps, trying to convince them to open their pocketbooks and donate.

And media outlets are already reporting on the campaign bank account horse race. While campaigns have evolved into machines that can raise tens of millions of dollars, the rules that govern the largest campaigns remain largely the same as they were 50 years ago.

"The fundamental disclosure process of disclosing who you get money from hasn't changed since Watergate," said Sarah Bryner, Director of Research and Strategy at Open Secrets. "All political candidates, parties, [political action committees] are required to file regular reports with the government saying who's giving them money."

But, she said, the changes that have occurred on the federal level have made the process more opaque.

"The biggest and probably meatiest [change] was the Supreme Court decision Citizens United versus the Federal Election Commission, which now is coming on its 15th birthday. And that didn't fundamentally change the disclosure process, but allowed for the creation of groups who could spend money on politics in unprecedented amounts."

She said that such groups do have to identify themselves in ads and disclose to somewhat of an extent where their money came from, those disclosures do not always prove transparent.

"Say I got money from a non-profit called something like Americans for a Better America. That [group] files with the IRS, but they don't have to disclose any information about who they are. So even though the political committee does provide public information, that public information doesn't necessarily tell a complete story."

Such moves are often referred to as dark money, and in 2022, Arizona voters approved a ballot initiative aimed specifically at tackling that issue.

Proposition 211 forced any group spending $50,000 or more in a state race or $25,000 on a local race to disclose its donors.

"It's only Arizona and it's only non-federal races," said the proposition's architect, former Arizona Secretary of State Terry Goddard. "What this new law will do is it basically says that if you're going to spend money for advertising for a candidate, you got to tell us who you are. You're going to tell us where the money came from."

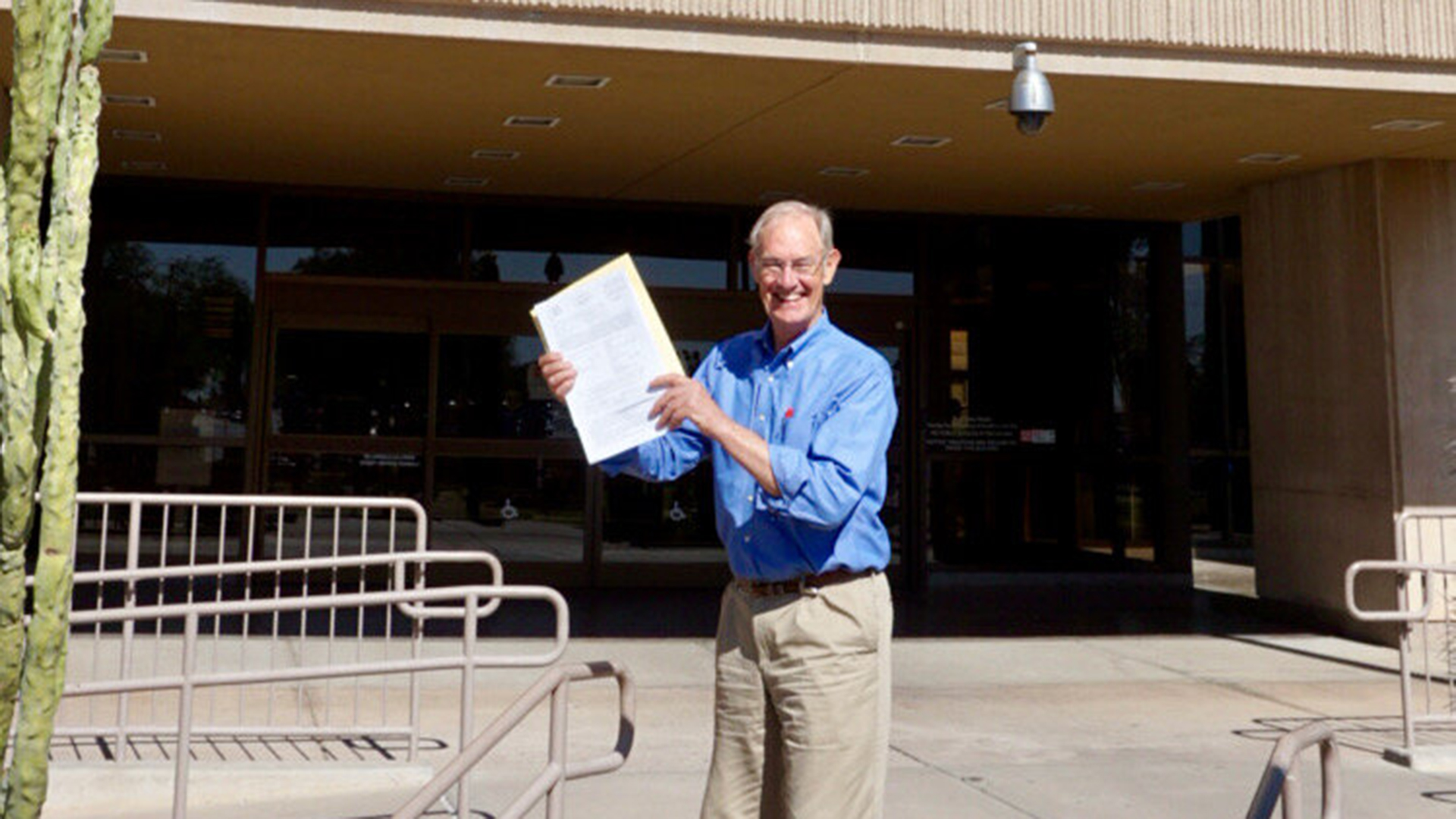

Terry Goddard poses for a photo just before turning in the paperwork that launched the 2022 Stop Dark Money Campaign.

Terry Goddard poses for a photo just before turning in the paperwork that launched the 2022 Stop Dark Money Campaign.

Prop 211 passed by a more than 2-1 margin, but has been the subject of lawsuits at the state and federal level since.

Despite those legal wranglings, the proposition is still in effect, according to its architect, former.

"There are a few individuals, a few corporations, who feel that they're special and that they don't want to have their names out in public, and so they use this dark money alternative. And that's what we're trying to stop. You've got to ask, 'What are they trying to hide?' If they're so afraid that having themselves affiliated with the candidate or proposition, is it because–and I suspect this is the case–they think that affiliation would do damage to the campaign they're supporting?"

Goddard said he hopes the law will have its intended effect, though it is likely that the campaign finance cat-and-mouse game of hiding donors will continue.

"I think people will be surprised. I think they will disclose. There are some where I think they are so adverse or believe that they're connection with a particular candidate or a particular cause would be so toxic, that they feel that they would do more harm than good by having their name identified. Some of those people will probably go away. I think it will continue and I think they'll continue the constant effort to try to hide in another way. I don't know what that trick is going to be but I'm sure it's coming."

While rules allowing dark money into politics have taken a step forward in Arizona, there are other ways in which campaign financing in the state remain opaque. One such issue was recently detailed in an article in The Tucson Agenda, a SubStack newsletter written by Curt Prendergast and Caitlin Schmidt, both formerly of the Arizona Daily Star.

Tucson Agenda's Curt Prendergast

Tucson Agenda's Curt PrendergastIt starts with the sentence, "If the goal of campaign finance rules is to keep voters from knowing who finances campaigns, then they’re doing a bang-up job."

The article notes that the timing of when campaign finance reports are released to the public and when voters receive mail-in ballots mean many cast their vote before this knowledge is available to the public.

Its example, the recently-completed primary election for Tucson's mayoral race and three city council seats.

"One of the things you want to know about an election is whose bankrolling the candidates," said Prendergast. "And so we go to the Campaign Finance page on the City of Tucson Clerk's office website, and the most recent campaign finance information that the voters have was from, like, the end of April. So a solid two months–the bulk of the campaign–there's just no information about money for voters to look at. The ballots had already gone out by that point."

Prendergast said that 46 percent of ballots in that election were returned before updated campaign finance information was released.

He notes that the reason for this issue is what state law says about when such reports have to be filed. It requires reports to be turned in no later than ten days before an election. Ballots are mailed out more than two weeks before that deadline.

"The question about everything to do with campaign finance is why are we doing it this way? We're talking about dates right now, but if you look at the reports that they file, they're all different from each other, it's like you have to have an accountant's degree to understand them. They're not designed for a voter to say, 'I got my ballot. I want to know who to vote for. This person bankrolled [this candidate]. Mo voter is going to do that. It's so unwieldy, and to even know where to look, that's why I wrote that lede."

Prendergast said it feels like some groups are doing the bare minimum to meet the statutory requirements.

"It's just bare bones. And I don't want to knock them too hard. To be fair, the City Clerk's website is getting better. They're at least trying, that's okay. But the entire system is geared away from the goal of voters should know who's financing campaigns."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.